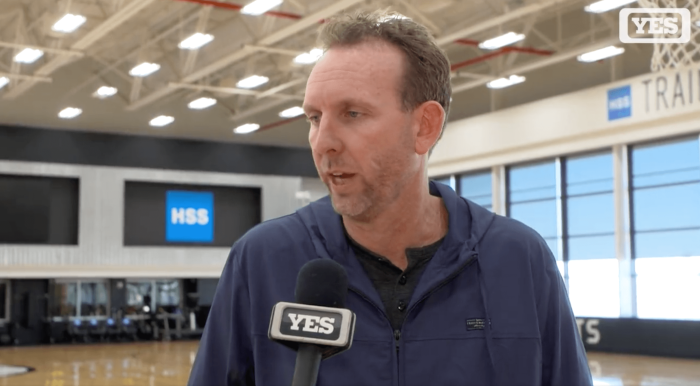

Jim Curtin has been with the Philadelphia Union for over 7 years now and his time with the club has grown more and more successful as times gone on. I decided to take a tactical deep dive into Curtin and more specifically, the tactics he’s brought to Philadelphia, how they’ve made the team successful, where Curtin’s influences come from and how much they’ve influenced his tactics and systems. In this article, I’ll be breaking down Curtin’s systems and tactics, both on and off the ball.

Jim Curtin: A Tactical Deep Dive

Let’s start off with Jim Curtin’s formation of choice. Some call it a 4-4-2 diamond, but it’s more of a 4-3-1-2 as the ‘wingers’ tend to come inside more and play as wider central midfielders. This gives the Union the flexibility to work the ball through the middle with numbers, or stretch the attack out wider and attack down the flanks.

Attacking Systems and Advancing Forward:

Now that we’ve established Curtin’s formation, let’s explore how the Union start their attacks off. When holding possession in their own half the Union will move their 4-3-1-2 formation into a 2-3-3-2 formation, where the full-backs push further up the pitch to give the ball carrying centre-backs more options if the holding midfielder is being marked closely.

Once the Union has moved forward into the opponent’s final third, the Union usually switches out of their 2-3-3-2 formation into two different systems, a 2-3-5 formation or a 2-3-2-3 formation. In terms of choosing which one they go into, it all depends on where the Union moves the ball.

Getting wide to create chances

If the Union moves the ball down the wider areas and wings, they’ll move into a 2-3-5 formation where the wider midfielders will turn into proper wingers and support the attack from there.

If they moved the ball down the middle of the field, the wider midfielders stay central, as they do in the standard 4-3-1-2 formation and place themselves behind the forwards, putting numbers in the middle of the pitch and acting as a link between the line of three and the forward line. This forms the 2-3-2-3 formation.

Attacking Midfielders Role:

One of the more interesting things about Jim Cutin’s system in Philadelphia is the way he uses the attacking midfielder behind the two strikers. This was Aaronson’s role before his transfer, but now Monteiro has taken over the role and if you watch them both closely, as the ball goes near the edge of the 18-yard box, they will join the two central strikers in the box.

Once they’ve joined the strikers in the 18-yard box, the three players will work together to constantly interchange their positions, you’ll never see them sticking to one position in different attacks. This creates constantly changing matchups with the opponent’s backline, something the opponent’s backline will hate because they can’t get used to one person’s specific way of attacking the ball, movement in the box, etc. Doing this disrupts the opponent’s defenders and confuses them in a way that can force mistakes, which can lead to goals. Pep Guardiola’s Barcelona team were the ones that made this most famous in modern era football.

Overloading defenses

In the examples below, you can see that having an attacking midfielder join the strikers in the box can allow the opposite winger to make a back post run, without being picked up by the right-back, who’s busy marking one of the three in the box.

Sometimes you’ll see the opposite winger make the run into the box, distract the wing-back, allowing the striker/attacking midfielder to ghost in at the back post.

Vertical Tiki Taka:

When tiki-taka football was first introduced to the world with Arsene Wenger’s Arsenal team, it took the footballing world by storm and many managers have tried their best to recreate this way of football. Fast, possessive football, where you keep the ball moving and wait patiently for a clear opportunity to score. Once again, Pep Guardiola was a huge pioneer in bringing this and even evolving it to a certain extent with both his Barcelona team and Manchester City team.

However, over the past few years, we’ve seen tiki-taka football evolve further than what Arsene made popular all those years ago, in a system called vertical tiki-taka. The essential philosophy of the two versions of tiki-taka football stays the same, fast, possessive football. However, the one difference is that in vertical tiki-taka, you don’t play safe, sideways passes to patiently wait to get a clear chance, you force those chances to appear with constantly moving forward and playing forward passes into space.

Vertical tiki-taka is more suited to what Jim Curtin plays in Philadelphia, the Union tries to get up the pitch, as quickly as possible and catch the defense off guard or disorganized. The midfielders hardly look to pass sideways to each other and, with the help of runs from both striker or the attacking midfielder, will look to put a ball through, in behind the defensive line. This acts as a very nice link to how Curtin sets the Union up defensively.

Defensive Organisation:

Jim Curtin and the Philadelphia Union take a very modern approach to the defensive systems and structure they implement. Curtin plays a very high line that looks to press as far forward as they possibly can. One objective of doing this is to pressure the opposition so much to force a turnover, but then they couple that with the vertical tika-taka to try and score as quickly as possible, given the defensive line will be out of shape.

The system works extremely well for the Union given the obsession that teams have with building out from the back. Using this system allows the Union to choke the middle of the field, with both strikers and the attacking midfielder forming a defensive triangle around the holding midfielder. With the holding midfielder out of the way, the opposition centreback has no other option than to go out wide to one of the wing-backs.

Springing the traps

With the opposition now forced out wide, the Union can spring traps on the opposition by the edge of the pitch. Once the ball goes out to the full-back, the striker that was marking the furthest centreback moves across and picks up the other central midfielder. The other striker sticks with the centreback that played the ball. The attacking midfielder follows the holding midfielder who moves across to offer support to the full-back. The wider midfielder is the one who really tries to pressure the full-back, and with a lot of his options completely suffocated out, turnovers happen and then the Union can push forward and take advantage of the out-of-shape defensive line.

The Union also uses this system to help them defend from throw-ins, given they can occur a lot from the situations I just mentioned above. The Union tries to form a pentagon type of shape to limit the time and space the opposition has to move the ball when it comes back into play.

Weaknesses in the System

The Union has had some great success using the system Jim Curtin plays and it’s a system that is set up to have a lot more success in the future. However, it’s not the perfect system as it doesn’t exist and so teams can find a way to counter the system.

One way of countering Curtin’s system is to play a back 3/5, having that extra centreback to go to when building out from the back allows you to attack the middle, from a different angle, without going into the Union’s wide trap system.

Another issue with the system is the space left across the pitch. In the wide areas, because they usually play a 4-3-1-2 system, with no true wingers and just wider central midfielders, it means the width of the team has to come from the right and left-back, leaving a lot of room down one of the flanks if the other team were to counter-attack.

Another example of how there’s a lot of space left on the pitch with the system Curtin plays is when the team is playing that high, counter-pressing style. Because the whole system is based on forcing a team down one side of the pitch and causing turnovers through suffocating the options around that specific wing-back, it means the Union has to commit more numbers on one side of the pitch compared to what their opponent has, to really have an advantage of them. With more bodies being in one area than the other, if the full-back can quickly spread the play, the Union are left in their own number disadvantage, further up the pitch.

Set piece problems

Set pieces have been a real issue for the Union in recent times too. I know I only looked at their throw-in defensive system, but their corner one isn’t as clear as a system as you’d hope. From the games I’ve seen, I’d say it’s a man-to-man system with the occasional player tasked with a zone to mark if every opposition player has already been picked up.

To start off, I hate giving any player a zone to defend from corners, it never seems to really work as you allow the opposition player to burst into that zone, unmarked and with every bit of momentum available. It can also cause confusion between two players in neighbouring zones, with players being confused about if they have to pick up a certain player, etc.

Honestly, from what I’ve seen, the Union is quite disciplined in their zonal defensive responsibilities, it’s the basic man-to-man system that they seem to be struggling with. If you look back at the 3-3 draw with Chicago, both Leon Flach, for the second goal, and Olivier Mbaizo, for the third goal, both failed to pick up their man when the ball came into the box. Given Jim Curtin is a former defender himself, I’m sure he realizes the issues with this and is making this a priority.

The main takeaway

Overall, I really like the formation, systems, and philosophies Jim Curtin implements with the Philadelphia Union. It’s fast, attacking football that’s fun to watch and you know you’re always going to see maximum effort whenever the Union plays. In the next article, it’s time to look at the first influence of Curtin’s style of play and the systems he implements. The influence I’m talking about is a former teammate of Curtin’s and a person who is taking European football by storm, any guesses?